This piece is adapted from “Defending the Humanity of Humanity,” a speech the author delivered Aug. 31 at Mut zur Ethik, a twice-yearly conference held in Sirnach, near Zurich.

Anyone taking up the question of our shared humanity in the late summer of 2024 must begin with mention of the Gaza crisis, or — with the escalating violence in the West Bank — the wider Palestine crisis.

These events are of world-historical magnitude. They challenge any idea of humanity we may have until now held as truths held to be self-evident, as we Americans would say.

That seems to be over now. It is as if an era in the human story has ended, and we enter upon one that requires us to think again, maybe for the first time since the 1945 victories, when those who came before us looked back upon the wreckage of the 1930s and 1940s and asked, “Where is our humanity?”

The events that lead us to this point are diabolic, something close to sheer evil. And how strange it is that the nation that leads us to this point represents the first half, the older half, of what we commonly call “Judeo–Christian civilization.”

Our shared task, in light of terrorist Israel’s war on the Palestinian people, is to begin the work — to wage another war, I would also say — in the cause of restoring our common humanity. This is a war against the indifference various forms of power incessantly encourage us to cultivate. To wage this war against power means learning from the crisis that defines our time — that makes this a world-historical moment — and then proceeding in a new direction.

There are different ways to think about this. “Defending the humanity of humanity” is something that must concern each of us as individuals. How many conversations have I had over the past 10 months, in how many different places, wherein people ask, “What can I do?” I cannot count them. Everyone seems to be asking this.

Posing the question is, of course, the first step toward answering it. Craig Murray, the Scottish activist and commentator, had a useful answer in a piece Consortium News published just a few weeks ago. “The paths of resistance are various, depending where you are,” Murray wrote. “But find one and take one.”

It is good, clear, properly demanding advice. Murray is writing about what we must require of ourselves as a matter of individual conscience.

I propose to turn the question another way, in the direction of what I will call our public selves, or our civic selves. I am thinking of public space, the institutions available to us through which to wage the war I just mentioned — the war against power in defense of our common humanity.

Bitter Reality

As I have mentioned in various commentaries, the Palestine crisis confronts us with a very bitter reality. This is the reality that, our democracies having devolved into “post-democracies,” none of the institutions through which we thought we could speak any longer functions in this way.

The institutions that are supposed to represent our will and aspirations are more or less broken. We have no way of expressing our objections to U.S. support for Zionist Israel’s genocide — no way that makes any difference, I mean to say.

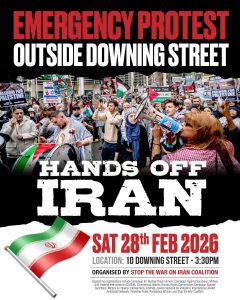

Vigil on Feb. 26 outside the Israeli embassy in Washington, D.C., the site of U. S. Airman Aaron Bushnell’s self sacrifice for peace the day before. (Elvert Barnes, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The majority of people in the West favor world peace, not war, to take another example. Surveys prove this. The majority of Germans favor co-existing, mutually beneficial relations with Russia. But in these and many other such cases, what the citizenry favors does not matter to those conceiving of and executing policy.

It is as if most people in the Western post-democracies were unaware of this condition, or only dimly aware of it, before the events of last Oct. 7, what has followed suddenly pushed this reality in our faces.

There is an extensive debate concerning whether ours is an age during which the nation-state is fated to pass into history, and I consider this an interesting discourse, but I will leave it aside for now.

I am concerned with the viability and potential effectiveness of what we call “the multilaterals” after many years during which they have been neglected, undermined, commandeered by the United States and its Western allies.

It is an excellent time to turn our attention in this direction as we think about defending humanity’s humanity. The 79th session of the United Nations General Assembly, which formally opened on Sept. 10, convenes its general debate on Sept. 24, which concludes on the 30th. Very few people take any notice when the G.A. meets each autumn. But I think this is about to change, or — better put — has already begun to change.

Secretary-General António Guterres, at podium and on screens, addresses the first plenary meeting of the 79th session of the General Assembly on Sept. 10. (UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe)

Among the many matters to be debated this year — sea rise and the climate crisis, nuclear disarmament, the use of antimicrobials for human health, the future of Africa — there is a two-day session called Summit for the Future to be held Sept. 22–23. Its topics will include “laying the foundations for a reinvigorated multilateral system.” So, the institution is talking about the institution, the system about the system. I read this, a new self-consciousness, as a very good sign.

Let us consider at this point the U.N.’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The G.A. advanced the UDHR in Paris on Dec. 10, 1948, just three years and two months after the U.N. was formally established. Here is Article 1 of the declaration. It is short and suitably to the point:

“All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.”

These principles are of eternal validity. But try to imagine any group of world leaders — or any Western leaders, more to my point — speaking in such terms today. This brief exercise gives us an idea of just where we are: a long way from home, I would say, in the matter of defending humanity’s humanity.

There are 30 Articles in the UDHR, all of them brief, some only one sentence. Article 6:

“Everyone has the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law.”

And some are remarkably pertinent to the crisis that defines our time. Article 15:

“Everyone has the right to a nationality. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality.”

I am well aware, as I imagine most people are, of how the U.N. has been undermined in the decades since its founding. Very soon after its founding the United States, in pursuit of the global hegemony it decided was its right after the 1945 victories, set about subverting its high purpose to serve its own.

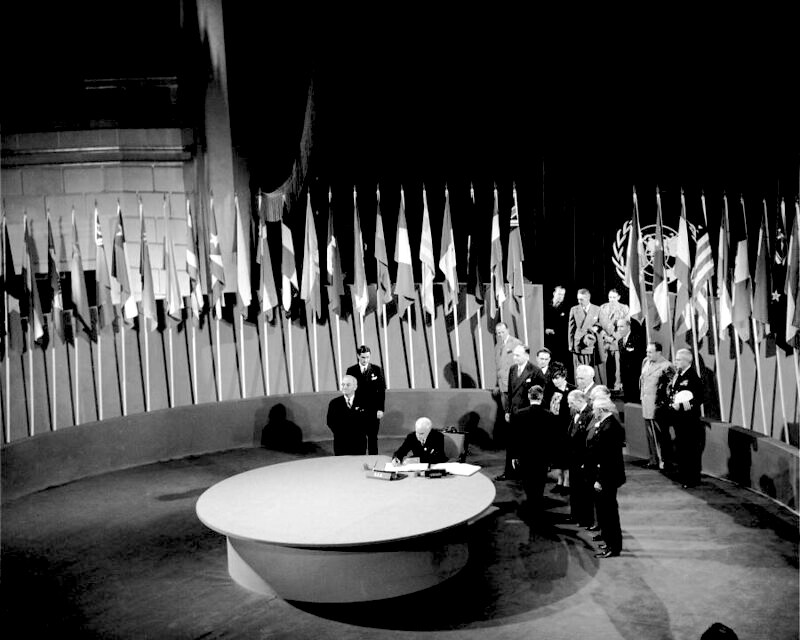

June, 26, 1945: U.S. Secretary of State Edward Stettinius, Jr., signing the U.N. Charter at a ceremony at the Veterans’ War Memorial Building. At left is President Harry S. Truman. (UN Photo/Yould,CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In Defeat of an Ideal (Macmillan, 1973), Shirley Hazzard, the late Australian writer, gave a good idea of the mess it had become two decades and some after its founding. Maybe you remember the statement of John Bolton, the repellent man the second Bush administration preposterously appointed as its ambassador to the U.N., to the effect that if the top 10 floors of the Secretariat in New York were removed it would make no difference. [See: The Pathology of John Bolton]

The gross abuse of the U.N. and its agencies is now common knowledge and may be — I have no way of measuring — something close to complete. The Americans’ well-known manipulation in recent years of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, the OPCW, is but one of very many contemporary examples.

[See: OPCW Execs Praised Whistleblower & Criticized Syria Cover-up, Leaks Reveal]

Again, it is interesting to reflect, with this corrosion in mind, on how very far we have come, and in the wrong direction, since the UDHR was written. Resisting the obvious causes for discouragement with which we live, we can then remind ourselves that the declaration was drafted in direct response to the catastrophes that led to the Second World War and implied in every syllable of it a belief in humanity’s shared capacity to right the wrongs that had so recently come close to destroying it.

Our circumstances are not so different now. America’s determination to prolong its global primacy has led the world to another point of danger such that violence and lawlessness have reached catastrophic proportions not so unlike those of the 1930s and 1940s.

The U.S. is now generally recognized, according to various surveys, as the primary cause of global disorder. We should see the Palestine crisis in this context. It is without question among the most egregious manifestations of American power in all of history. And it is in response to this, direct response, that we find new and very important efforts to reconstruct the “global commons” that the founding of the United Nations represented.

Just a few years ago a number of nations, all of them non–Western, formed a group advocating a return to the U.N. Charter as the basis of international law and the conduct of U.N. member states. This was not a very large group, and so far as I know it has not made a significant mark in and of itself.

It is the intent I wish to draw to your attention. The members of this group included, among others, Russia, China, India, Brazil, and I think South Africa. We know from things stated at the time that these nations acted in response to the wild disorder occurring as the U.S. advanced its now-infamous “international rules-based order.” The world had become too dangerous for these nations not to act.

I recall when Moscow and Beijing issued their Joint Statement on International Relations Entering a New Era, in February 2022, that it was very clear they did so in part because they had become genuinely alarmed that the disorder of “the rules-based order” had become a grave danger to global stability. I still consider the Joint Statement the most significant political document to be made public so far in this century.

[See: PATRICK LAWRENCE: ‘Primacy or World Order’]

We now speak familiarly of an emerging “new world order,” an order worthy of the term. And in the years since the Joint Statement we have seen the markedly rising influence of organizations such as the BRICS. We should understand these developments as of a piece with the small group calling for the restored primacy of the U.N. Charter and the Sino–Russian initiative. When we see them in this way they provide us with a pole we can use to reshape our thinking.

Shanghai Cooperation Organization Secretariat in Beijing, 2022. (N509FZ, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

This requires that we push aside the waves of propaganda that inundate us daily — anti–Russian, anti–Chinese, altogether anti-the non–West — while also setting aside what objections we may have that the forms of government we find among non–Western nations do not match ours: Our forms of government, after all, do not any longer match ours, do they?

And then we can recognize that the new efforts I describe very briefly are at bottom in the cause of the validity and purpose of multilateral institutions and altogether the betterment of humanity — in my terms today in defense of humanity’s humanity.

I know all about the charge that these thoughts are hopelessly idealistic, a token of sheer naïveté and of misplaced trust. These are the thoughts of those who cannot see forward, nothing more. Why, to put this matter to rest, do none of the Western post-democracies, rather than mouthing empty platitudes, stand squarely for a restoration of the principles embodied in institutions such as the U.N. and expressed in the U.N. Charter?

I am suggesting, in short, that a reform movement to revive our too-long-abused global institutions is afoot and merits serious attention. A page is turning, to put this point another way. And apart from the examples I have just cited, a lot of good people are getting a lot of good thinking done.

The other day Jeffrey Sachs, the scholar, author, and prolific commentator, privately circulated a paper he calls, “Achieving peace in the new multipolar age.” It goes straight to my point. Sachs notes America’s declining share of global gross domestic product, its overstretched military, and its perennial budget crisis, and concludes, “We are already in a multipolar world.”

What kind of world will this be, he asks, and he then outlines three possibilities: One is continued great-power rivalry. The second is, as he puts it “a precarious balance of power.” It is the remaining idea that he favors and that interests me:

“The third possibility, scorned in the past 30 years by U.S. leaders but our greatest hope, is true peace among the major powers. This peace would be based on the shared recognition that there can be no global hegemon and that the common good requires active cooperation among the major powers.

There are several bases of this approach, including idealism (a world based on ethics) and institutionalism (a world based on international law and multilateral institutions).”

I admire this observation for its combination of things we do not commonly think of together. In so many words, Sachs is writing about a world order in which humanity’s humanity is recognized as paramount and defended.

Secretary-General António Guterres, second from right, greets Philemon Yang, president-elect of the 79th session of the United Nations General Assembly, in June. (UN Photo/Evan Schneider)

Other analysts are digging deeper now into the structural flaws requiring repair if the U.N. is to fulfill anything like the role for which it was initially intended. Some of these date to the U.N.’s founding Charter. But a good thing it is, and a measure of our moment, that these matters are at last raised.

Hans Köchler, an eminent scholar who presides at the International Progress Organization in Vienna, put out a brief paper last week, “Sovereignty and Coercion,” in which he identifies “a fundamental inconsistency in the organization’s rules and procedures.”

The G.A., he means to say, embodies the U.N. Charter’s principle of equality among nations, but power in the U.N. structure is vested solely in the Security Council. In this passage he describes what amounts to — some disturbing echoes here — a “state of exception” wherein those who make and enforce the law are not subject to the law:

“A certain category of members of the supreme executive organ of the U.N., vested with vast coercive powers to enforce the ban on the use of force, can under no circumstances be legally coerced to abide by the law. For those countries, namely the five permanent members of the Security Council, ‘sovereignty’ appears to be exclusive, in stark contrast to the Charter’s principle of ‘sovereign equality’ of all member states.

For the P5, the provisions of the Charter mean sovereignty in the sense of absolutist rule: the power to coerce, linked with the privilege not to be coerced. In other words: The law cannot be enforced against a permanent member, or an ally enjoying the protection of a permanent member.”

A book arrived just as I was composing these remarks that I take to be the most thorough treatment we have of the reform question. Richard Falk and Hans von Sponeck both served in the course of their careers as high U.N. officials. And they spent five years on Liberating the United Nations, which Stanford University Press has just published with the interesting subtitle, Realism with Hope.

This is part history and part prognosis. Falk and von Sponeck begin as I have, noting the unfortunate extent to which the U.N. is, as they put it, “less relevant as a political actor today than at any time since its establishment in 1945.” They then proceed through a lengthy account of how this state of affairs came to be, and I admire their unsparing honesty as they do so.

Then they rotate their gaze and tell us,

“We believe that there will arise a new movement for revitalizing democracy, a stronger U.N., and a more benevolent global leadership, and we write with faith that in the end prudence, rationality, empathy, expanded time horizons, and mechanisms facilitating cooperation and imposing accountability will emerge.”

I take issue with only two things in this wonderful statement of purpose and expectation. No need for the future tense when looking for a movement for reform at the U.N.: This is already evident, and these two long-respected professionals are part of it.

Equally, however high we may hold faith as we look at life and find our ways through it, the world Falk and von Sponeck anticipate will not come about by way of faith. It will come about as a result of what each of us determines to do to bring it about in our common defense of the humanity of humanity.

Patrick Lawrence, a correspondent abroad for many years, chiefly for The International Herald Tribune, is a columnist, essayist, lecturer and author, most recently of Journalists and Their Shadows, available from Clarity Press or via Amazon. Other books include Time No Longer: Americans After the American Century. His Twitter account, @thefloutist, has been permanently censored.