Embarking on a process of personal, individual “de–Westernization” is absolutely essential if we propose to defend the humanity of humanity.

This is an edited version of the second of two lectures the author gave recently on “Defending the Humanity of Humanity.” He spoke Oct. 10 at Mut zur Ethik, a twice-yearly conference held in Sirnach, near Zurich. His first lecture can be read here.

Bust of Herodotus. (Bradley Weber, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

By Patrick Lawrence

Special to Consortium News

The barbarities of Zionist Israel force fundamental questions upon us: Where is our humanity as the Israelis prosecute their terror campaigns before us daily? What shall we do as we find ourselves powerless to react meaningfully because, as the West Asia crisis has suddenly forced us to realize, our institutions have failed us?

Now many of us recognize the need to defend our humanity — the humanity of humanity, as I think of it.

I previously addressed this question as it relates to public space and argued that it is time to look again at multilateral institutions, the United Nations chief among them, with a view to reviving them after a long period during which they have been discounted and devalued.

Now I want to turn the questions just posed in another direction and suggest we consider the matter from a personal, individual perspective.

What must each of us do, in the privacy, so to say, of our consciences, our thoughts, our surmises and judgments, to take up the work of defending humanity’s humanity? It is at bottom a psychological question. It is a matter, very simply, of “changing our minds.”

We must begin, it seems to me by recognizing who we think we are. Note right away: I speak not of who we are but who we think we are, who we assume ourselves to be.

We live in “the Western world,” as it is called, and it follows naturally we are Westerners. Who can argue with this? To be Westerners is absolutely integral to our identity, I think I can say without further explanation.

This has been so for many centuries. I take my date in this connection to be 1498, when Vasco da Gama set foot along the Malabar Coast, in southern India, making himself the first modern Westerner to arrive in the non–West.

And then it follows easily enough that when we declare what we are we declare what we are not. I have just suggested the result: The world is divided between Westerners and non–Westerners. This division, fundamental as it is to how we think, is by and large the West’s doing. Let us take care to note this.

This line between West and non–West is very old, going back much earlier than 1498. It dates at least to the 5th century B.C., when Herodotus recorded the Persian Wars in his famous Histories. And it is remarkable how intact this line between West and East comes down to us.

The Biden regime and the rest of the West think of it today as the line dividing democracies and autocracies. Cast the Israel–Palestine question in a larger context and you find that, whatever else it is, it is another confrontation between West and non–West.

Ruins left by Israeli airstrikes in Khan Younis in the southern of Gaza strip, On Oct. 8, 2023. (Mahmoud Fareed, Wafa for APAimages)

We may not accept the Biden regime’s contention that it is waging war against the non–West’s autocrats in behalf of the West’s democrats, but this does not mean we do not nonetheless conceive of ourselves as fundamentally “Western.” We have in this way inherited our past, consciously or otherwise.

We come to my first fundamental point. If we are to defend the humanity of humanity, our first obligation is to recognize that the line between West and East is, as it has always been, a human construct and nothing more. Herodotus, in his wisdom, made this point: Even as he recorded the half-century of enmity between the Persian Empire and the Greek city-states, he called the line between them, dividing East from West, “imaginary.”

Nobody seems to have got this point over the past 2,500 years: It is commonly assumed today that this line is etched immutably into the earth, as if it would be visible from a satellite. So we must begin by disposing of this unexamined thought. It is a question, then, of — very literally — “changing our minds.”

This means, and let’s invent a useful word here, we must “de–Westernize” our consciousness. I suggest to you that embarking on a process of personal, individual “de–Westernization” is absolutely essential if we propose to defend the humanity of humanity.

The Japanese — the early Japanese feminists, actually — had a wonderful expression for this kind of project. These were superbly human people —principled, authentic, at ease among strangers such as I was — and I learned a lot from them. They spoke of “the edifice within” and the need to dismantle it.

As things stand the Biden regime and its clients are dedicated now, just as they will tell you, to defending the West as their primary responsibility. When we de–Westernize our consciousness we can easily see through this thought and understand how pitifully shallow and limited it is.

Instantly, we have opened the door for ourselves to defending not the West — the implication being the West against the rest — but humanity and the humanity of humanity.

Let me say this straightaway. Jens Stoltenberg, the secretary general of NATO, and Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, and Antony Blinken, the U.S. Secretary of State, are in great, obvious need of de–Westernization. But let us not make the mistake of assuming it is these few unreconstructed Western supremacists who constitute our problem.

I am talking about a new inner attitude, a new way of thinking, seeing and doing, that all of us must cultivate in ourselves. This is nothing like impossible, should anyone here wonder as to the formidability of the task.

Here I speak from experience. I spent just short of three decades as a correspondent abroad, almost every day of it in non–Western nations, mostly but not only in East Asia. And when I finished those years I discovered, a little to my surprise, that I was no longer truly a Westerner.

My physiognomy — round eyes, fair hair, and so on — had nothing to do with it. I was entirely myself, of course: I had surrendered or disavowed nothing. But I had “changed my mind” — or life and experience had changed it for me. I was no longer entirely Western. It had to do with the way I thought, the way I saw the world, and how I acted in it.

The thought that the West was superior to all those gathered in the name of the non–West, had come to seem to me ridiculous. The Western insistence on the primacy of the individual seemed to me problematic at the very least, especially as Americans thought of the matter.

I am not suggesting one must spend three decades wandering among Asians to accomplish the project of de–Westernizing oneself. Not at all. It is a question of cultivating one’s self-awareness. What matters is one’s honesty, one’s independence of thought, and one’s determination to be nothing more nor less than oneself regardless of prevailing orthodoxies.

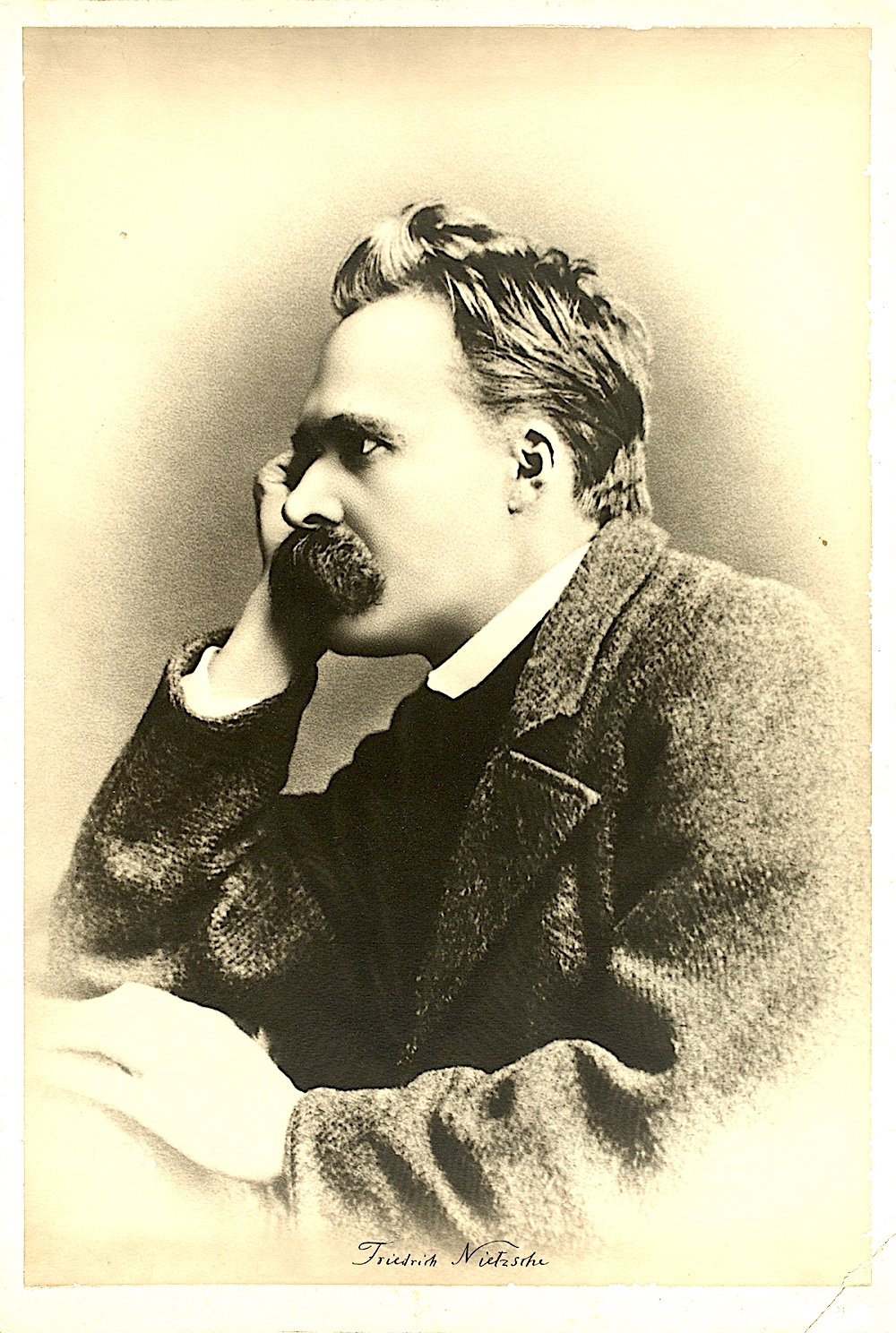

Friedrich Nietzsche wrote somewhere — The Gay Science, perhaps, and I am sorry I cannot be more precise — of “taking off the garb of the West,” a wonderful way of putting it. And somewhere else he wrote of rowing our boats out beyond our shores so we can look back from a useful distance, and see ourselves as we are.

This is part of what he meant, and only part, by “the pathos of distance.” Only from a distance, he thought, can we see our flaws and altogether ourselves. And this is what I mean — to reconsider who we are, top to bottom. Again to Nietzsche, it is part of what he meant when he wrote of “the revaluation of all values.”

He urged us, as I put it, to skate out on the thin ice of the modern age and think again of all we have assumed to be so.

Portrait of Nietzsche in 1882 by Gustav Adolf Schultze. (Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

I will turn here to some specific steps I think we need to take. They are all aspects of what I think is the fundamental process to which we must submit ourselves as individuals. This we can easily name: Let’s call it “the process of overcoming,” or maybe “self-overcoming.”

The first of these matters I have already suggested. It concerns the ideology that binds the West as we have inherited it, even if this ideology resides within our unconscious.

To defend the humanity of all humanity requires us to overcome in ourselves all the presumption that our ways of life and our institutions are the superior paradigm to which others aspire, or, if they do not so aspire, they ought to aspire, or at the extreme, they must be taught or made to aspire, and if they do not so aspire it is only because they are primitive and, so, ignorant.

The purest expression of this presumption I know of is called “Wilsonian universalism,” after the president who advanced the idea in the early years of the last century. We — we Americans — are humanity’s gifted ones, Woodrow Wilson professed, and it is our responsibility to spread our light to all the dark corners of the world.

It is easy to deceive ourselves as we consider this point. It is easy to say, “How foolish and extravagantly narcissistic a thought.”

I know this because, during my years in Asia I discovered many times, and always bitterly, that I had been fooling myself when I assumed I held to the equality of those among whom I lived. When I look back now I am ashamed at the many occasions when my true views of others emerged and turned out to be nothing like what I thought they were. They seemed, on the worst of these occasions, even a touch Wilsonian.

It takes, as I suggested just earlier, a kind of raw honesty to look at ourselves, to look within, and see exactly who we are and what it is we have to overcome.

It is a question of shedding an ideology within which we have been immersed the whole of our lives. And if you have breathed a certain kind of air or drunk a certain kind of water the whole of your life, it is difficult indeed to imagine any other air or water. But this is what we must do.

The second matter I want to raise has to do with politics. Here I have a couple of points to make.

We hear a lot these days about inclusivity and diversity. We hear so much about these things it is difficult to take these words seriously. Listen closely. The people who speak most loudly about diversity and inclusion are typically talking about skin color, gender, or some other superficial marker of identity.

They entertain no notion whatsoever of inclusion or diversity when it comes to any substantive value. One can be different in all sorts of ways, but not, heaven forbid, different in thought or belief or tradition or culture.

This is of no use. If we are to defend humanity’s humanity we must take back these words from the supercilious people who use them most — who make them mean their opposite, indeed — and make them mean something new and serious.

This requires not merely accepting but embracing true diversity and true inclusion, and this means, in turn, embracing those who may not think at all like us, or whose values are fundamentally at odds with ours.

And the more we find others to be strangers in these ways, the more important it is for us to overcome our proclivities.

My third concern here is maybe the most important. Perhaps I should have put it first. This has to do with history. History, as we will always find in all circumstances, is once again our friend.

We share a tendency across the West to ignore or dismiss the histories of non–Western peoples. If you doubt I am being fair in saying this, pick up a mainstream newspaper and study how it treats Palestinians, Iranians, Russians, Venezuelans.

Note my choice of examples. Our societies are typically inclined to erase the histories of those we stand against. This is a very pernicious practice leading to all sorts of problems. Deny the history of another people and we deny those people — their complexity, their aspirations, indeed, in the end their humanity.

We so license ourselves to affix a label to them — “terrorist state,” “oligarchy,” “theocracy,” what have you — and there is no more need to understand them. Their histories instantly disappear. We have, in a word dehumanized them.

The obvious project here is to allow others their histories. This is instantly transforming. Look what happens in the ready-to-hand case of the Palestinians of Gaza, when we put the present crisis in the context of 1948.

Israeli damage to Gaza, January 2009. (DYKT Mohigan, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

Our understanding is immediately changed. We have, in our terms today, de–Westernized our perspective on this question. And this is why, I have to add, we are encouraged — incessantly, relentlessly, every day — to leave the history of this crisis out of it.

If we are to defend the humanity of humanity properly, we must be willing to acknowledge that humanity has countless different histories, all of which we must honor as valid. In this cause I urge we make ourselves vigilant, vigorous defenders of history, insisting, in whatever circumstance we find ourselves, that it can never be left out.

As another example of what I mean, we must look at a nation’s system, a system such as China’s, and refrain from concluding without elaboration or reflection that it is objectionably “authoritarian” and content ourselves to say it is run —as I read in The Times of London the other day — “by a totalitarian clique.”

If we propose to defend humanity’s humanity and indeed our own, to think in this way is a hopeless case. It is failure right out of the box. This may be what China looks like to the unreconstructed Western mind, but it amounts to a cartoon rendering of reality. It is no longer acceptable, if ever it was, on two grounds.

One, if we persist in cultivating our blindness to this extent we will lose touch with the 21st century and all its currents. Two and more obviously, we will fail utterly to understand others.

In the case of China, you have to look not at a map of the mainland, one, but a great pile of maps from different periods. Then you see that China has a long history of tension and conflict between integration and disintegration, going back many centuries, such that the China of one period scarcely resembles the China of another.

Maintaining territorial integrity and defending China’s sovereignty has been a constant challenge over a long, long period of time. With these maps and what we learn from them in mind, we can understand why a strong centralized government has been so long part of Chinese reality and why it is broadly accepted even among Beijing’s domestic critics.

And we can then see that the unity and integration of the present-day People’s Republic is a great achievement.

Lightning over China and Taiwan, July 27, 2014. (NASA, International Space Station, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

As part of this achievement, I will add, we find the guiding precepts by which modern China conducts itself among others. I am thinking here of Zhou Enlai’s famous Five Principles, formulated in 1954, about which most Westerners know as much as they know of Chinese history — more or less nothing.

Respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty, non-aggression, noninterference in others’ internal affairs, interacting to mutual benefit, peaceful coexistence: This makes five. These are irrefutably admirable ideas.

They are 21st century ideas, too. And they arise out of China’s long experience throughout its history.

As I reflect on them, I will mention, another passage in Nietzsche comes to mind. I have a lot of “Fritz,” as his family called him, for you today, because he was greatly concerned with the matter of what made us Western and the need to transcend our “Westernness.”

A word often associated with him is “perspectivism.” It means the capacity to see from the perspectives of others, and I have long argued this is paramount among our imperatives if we are to make any kind of success of the 21st century.

This is from Twilight of the Idols. It bears more or less directly on our task of de–Westernizing ourselves:

“The whole of the West no longer possesses the instincts out of which institutions grow, out of which a future grows: Perhaps nothing antagonizes its ‘modern spirit’ so much. One lives for the day, one lives very fast, one lives very irresponsibly: Precisely this is called ‘freedom.’ That which makes an institution an institution is despised, hated, repudiated: One fears the danger of a new slavery the moment the word ‘authority’ is even spoken out loud. That is how far decadence has advanced in the value-instincts of our politicians, of our political parties: Instinctively they prefer what disintegrates, what hastens the end.”

Think about this. These are the remarks of someone who has rowed his boat beyond the shore, turned back, and saw something other than what he was supposed to see.

I have one further point to make in the matter of history.

When I urge we value and defend it, I do not mean merely remembering. Memory and history are closely related, and this relationship is among my favorite topics. Here I will say only that when we speak of defending history and making use of it, I mean making sure we attend to written history. We must insist on de–Westernizing our histories by insisting that events now neglected— al–Nakba a prime example — are neither minimized nor distorted nor excluded altogether.

Arab labor organizer Monadel Herzallah at Nakba at 60 concert in San Francisco Civic Center, May 2008. (Hossam el-Hamalawy, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

When Nietzsche wrote of taking off the garb of the West he did not mean we had to forget who we are or in any way surrender our identities. Quite the opposite. The exercise was intended as a process of self-discovery, not self-denial. Culture is part of what it means to be human, and as we learn to honor the cultures of others we must also honor our own.

And so, as we think about de–Westernizing our consciousness we must also think of “re–Westernizing” ourselves.

Here I want to put forward a radical idea.

In the mid–19th century, as the West was industrializing and learning to place its faith in science, the Enlightenment, the Age of Reason, gave way to the Age of Materialism. Our age is an extension of this latter, fair to say. Material consumption is an abiding value now. We honor the market as if it always knows best — as if it can do our thinking for us, as if what the market dictates will always yield the right outcome.

We have, in other words, more or less lost sight of the ideals of the Enlightenment. We profess to live by them, but as I noted in an earlier lecture, every age professes rather hollowly to honor the values of the preceding age even as it has abandoned them.

Daylight Music – Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment Experience Ensemble in London, January 2016. (Paul Hudson, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

Here I will invoke Nietzsche’s notion of the revaluation of all values.

When I speak of re–Westernization as the companion of de–Westernization, and both in the cause of defending the humanity of humanity, I am proposing nothing less than the transcendence of the values we inherit from the Age of Materialism and a return to the ideals our societies left behind when, as Western nations industrialized, “progress” acquired aspects of an ideological cult. We have ever since mistaken material progress for progress by way of our values — the progress altogether of humanity.

We are left now with all the gadgets we can think of but, as the Zionists grimly remind us, we find our conduct toward one another as barbaric as it ever was. Steve Jobs used to boast that Apple was going to “change the world.” How impoverished can our thinking get? Technologies — cellular telephones and all the rest — have changed nothing that has to do with human values. If you consider the Gaza case, technologies have changed the world by going some way to destroying human values.

The Enlightenment’s ideals — humanism, rational thought, natural law, toleration, “liberty, equality, fraternity,” and so on — are what we in the West can bring to the world not unlike the way China offers the world its Five Principles. I am not talking about, I must hasten to add, any kind of nostalgic return to the past. I am talking about a return to ourselves.

Here I have to take care to qualify my thinking.

There are some very intelligent people who tell us that the Enlightenment project was, in fact, a misconceived failure and the source of a lot of the problems humanity has since faced. It was from the Enlightenment, this argument runs, that there arose the impulse to universalize Western civilization as the glorious destination of all humanity. The extent to which Enlightenment thinkers such as Thomas Jefferson elevated the individual to a position of sovereignty seems to me another problem.

John Gray, a British intellectual, published a book called Enlightenment’s Wake in 1995 and in it went a long way toward demolishing commonly accepted notions of what the Enlightenment was about. I not only acknowledge this line of thinking. I endorse many aspects of it.

And this is why I bring Nietzsche’s notion of revaluing our values into the matter. The Enlightenment’s ideals are enduring. It is how they were interpreted and applied that produced the failures. Ho Chi Minh admired Jefferson’s Declaration. But America betrayed Ho, let’s not forget. Jefferson, to go straight to the point, was a slave owner.

I speak, then, of the manifestation of Enlightenment values in a new, 21st century context. This may appear a bold idea, but there is nothing terribly complicated here. Advancing beyond the values of the Materialist Age is, yes, a new thought. But I am talking merely about revaluing — and so living up to —ideals we continue to profess but abjectly fail to honor. Living up to these ideals means, before it means anything else at all, acting according to them while not imposing them on anyone else. You cannot profess liberty — and certainly not democracy — while insisting others accept your version of these.

This is what I mean by “re–Westernization” as the companion of our de–Westernization project, and both in the cause of defending the humanity of humanity.

Patrick Lawrence, a correspondent abroad for many years, chiefly for The International Herald Tribune, is a columnist, essayist, lecturer and author, most recently of Journalists and Their Shadows, available from Clarity Press or via Amazon. Other books include Time No Longer: Americans After the American Century. His Twitter account, @thefloutist, has been permanently censored.